The Cop29 climate talks in Baku focus on establishing a new climate financing target to replace the $100 billion annual commitment, which expires this year. Advocates are calling for increased contributions from wealthy nations and a shift towards private capital involvement in climate initiatives. However, concerns persist regarding the burden of loans on developing countries and the necessity for polluters to pay their fair share, leading to proposals for climate taxes and new funding mechanisms.

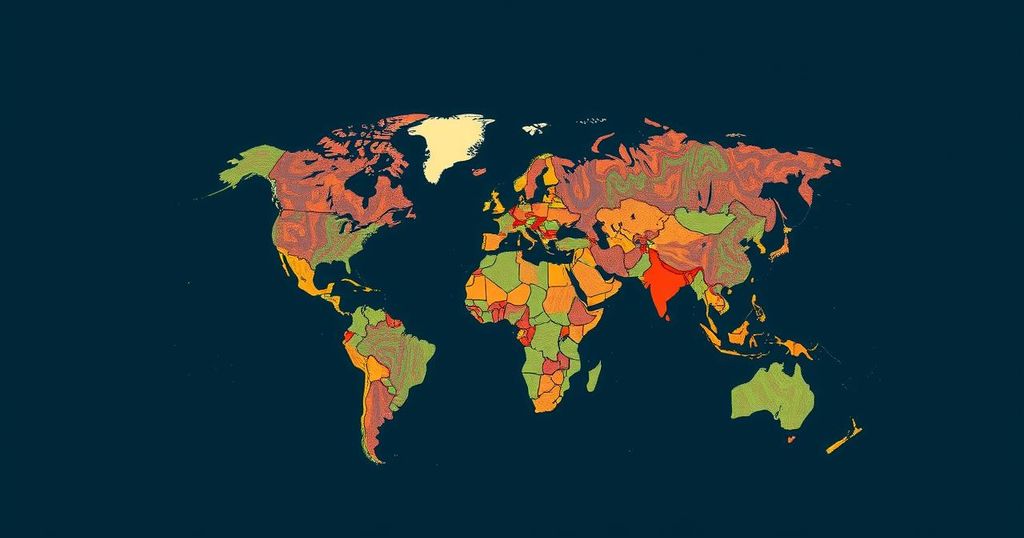

This week in Baku, Azerbaijan, the UN’s Cop29 climate talks are convening approximately 50,000 stakeholders, including government officials, investors, and activists, to address a significant financial query regarding climate assistance for developing nations. The conference aims to establish a new annual climate financing target to succeed the existing $100 billion pledge, which was set in 2009 and is set to expire at the end of this year. Current climate finance provisions fall significantly short in supporting vulnerable countries facing mounting climate challenges, having been fully met only once since its inception, namely in 2022. Advocates are urging wealthy nations to agree upon a new collective quantified goal for climate finance, with anticipated contributions ranging between $500 billion and $1 trillion annually, although some projections suggest figures may exceed $5 trillion. “Setting a more ambitious goal will be essential to helping vulnerable countries adopt clean energy and other low-carbon solutions and build resilience to worsening climate impacts,” remarked the World Resources Institute. Traditionally, financial assistance for low-carbon initiatives has stemmed from high-income countries, such as the United Kingdom, United States, Japan, and Germany; however, emerging economies like China, India, and South Korea are now essential players in global emissions, challenging the existing paradigm. Discussions are likely to include extending the pool of contributors to climate financing, while simultaneously acknowledging that the required financial resources surpass government budgets. Consequently, talks are focused on modifying global climate lending structures to harness private funding sources. Stephanie Pfeifer, head of the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change, indicated that global investors are increasingly seeking methods to mobilize capital for climate finance, emphasizing that an ambitious goal which incorporates private investments can advance environmental targets in developing nations. However, this approach has faced criticism from various non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which assert that loans could exacerbate the debt burden of developing countries that are least responsible for climate change yet most affected by it. Debbie Hillier of Mercy Corps stated, “Climate finance is not about charity or generosity but responsibility and justice,” highlighting the need for serious financial contributions from the major polluting nations. To further this objective, a proposed Climate Finance Action Fund (CFAF) could rely on voluntary contributions from fossil fuel-producing nations and corporations for financial assistance in climate projects for developing countries. For entities resistant to financial contributions, environmental organizations advocate for the implementation of climate taxes. Notably, the group 350.org is targeting wealthy individuals and major fossil fuel companies for their disproportionate environmental impact in a planned accountability campaign. The funds generated from taxing affluent individuals could serve domestic climate initiatives and bolster international climate finance efforts. A forthcoming report from Oxfam is anticipated to reveal widespread public support in the United Kingdom for increased taxation on high-end emissions sources, such as private jets and superyachts, indicating a societal push towards accountability in climate responsibility.

The UN climate negotiations have historically aimed at addressing the significant challenges posed by climate change, particularly for developing countries that often bear the brunt of the impact despite contributing minimally to global emissions. The existing commitment of $100 billion per year, established in 2009, is considered insufficient for the evolving needs of these nations. As climate change intensifies, calls for increased financial support from wealthier nations have become more pronounced, necessitating a shift in how climate financing is conceptualized and funded. With emerging economies stepping up their economic and environmental impacts, discussions at Cop29 include reevaluating which nations should contribute to global climate finance.

In conclusion, the Cop29 climate talks in Azerbaijan represent a critical turning point in the global climate finance discourse. Stakeholders are seeking to significantly enhance the financial support available to developing nations, addressing their increasing vulnerability to climate change impacts. The discourse surrounding who should finance climate action is evolving, with potential contributions from both high-income countries and private sector investments coming into play. However, critics warn against placing additional debt burdens on struggling nations, instead calling for accountability from those most responsible for climate emissions.

Original Source: www.theguardian.com