The article discusses how the predominance of English in climate science creates significant barriers to understanding and accessing vital climate information for the majority of the global population. While English accounts for approximately 90% of scientific publications, this linguistic disparity fosters broader inequalities and limits the ability of those in developing nations to engage with climate research. Initiatives like UNESCO’s Open Science and organizations such as Climate Cardinals aim to promote multilingualism and improve access to climate information.

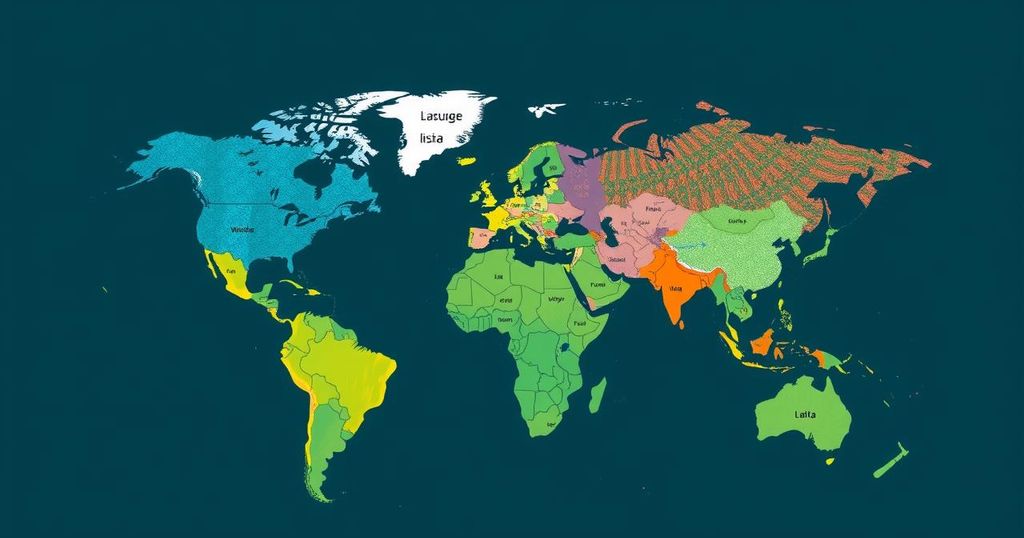

The burgeoning crisis of climate change has emerged as one of the most pressing global concerns of contemporary society, necessitating equitable access to climate science literature. While scientific discourse about global warming predominantly occurs in English, this phenomenon paradoxically exacerbates the accessibility issue for the majority of the world’s population. To elucidate this paradox, one must acknowledge the staggering statistic that approximately 90% of scientific publications are composed in English, creating a linguistic barrier that alienates significant portions of the global populace, particularly those for whom English is not a native language. The demographic statistics reveal that English, despite its title as a global language, is primarily spoken within a limited geographical scope – notably countries such as the United Kingdom, Ireland, the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, whose combined populations barely represent 400 million individuals out of nearly eight billion worldwide. In regions where English coexists with indigenous tongues, it frequently serves as an elite mode of communication, accessible primarily to urban, educated classes. Thus, the considerable number of individuals proficient in English is thus estimated at around 1 to 2 billion, meaning a vast majority—three out of four people—remain unacquainted with the language in which climate discourse is largely conducted. This linguistic disparity not only inhibits the distribution of vital climate knowledge but also perpetuates broader cultural and scientific inequalities. Predominantly, scientific literature is generated in Anglophone countries, especially the United States and the United Kingdom, which disproportionately controls prestigious scientific journals. Consequently, communities most afflicted by climate change, particularly in developing nations, often lack access to critical research that pertains to their own ecological circumstances. In response to these challenges, initiatives such as UNESCO’s Open Science are pivotal. These initiatives strive to democratize scientific knowledge, advocating for multilingual approaches that allow scholars worldwide to contribute research in diverse languages beyond English. Additionally, advancements in machine translation technology present an opportunity to expand accessibility. Organizations like Climate Cardinals are actively working to translate climate information into over one hundred languages, facilitating greater inclusivity in the climate movement. Through these earnest efforts and technological innovations, there lies a promising path towards enhanced climate literacy, which may ultimately catalyze collective action to address the gravitas of climate change.

Climate change is recognized as a critical global challenge, impacting all aspects of human life across the globe. As scientific understanding and discourse regarding climate issues are predominantly conducted in English, a considerable portion of the global populace remains disconnected from crucial information due to language barriers. This situation not only highlights a significant inequity in knowledge dissemination but also suggests that those who suffer the most from climate consequences, particularly in developing regions, have limited access to scientific research.

In summary, the predominance of English in climate literature constitutes a formidable barrier to global climate literacy. The ongoing efforts to promote multilingual communication and harness the potential of technological advancements represent crucial steps toward dismantling this barrier. By ensuring that climate science is accessible to all, regardless of linguistic background, we can foster a more informed global community capable of proactive engagement in climate action.

Original Source: theconversation.com